INSPIRATIONS

Sahaj Vision – The Bauls of Bengal

“Everything exists for the humor of God. It exists because God created the universe to enjoy.”

Walking across the tarmac at the Kolkata airport in late December 2007, our senses were inundated by the thick, haunting atmosphere—a collision between the cool misty morning air and a heavy pall of gray smog. On the way into the city, we passed dust-laden tropical canopy and glistening pools, where people squatted with bronze pots at the edge of a pool to get water or wash clothes.

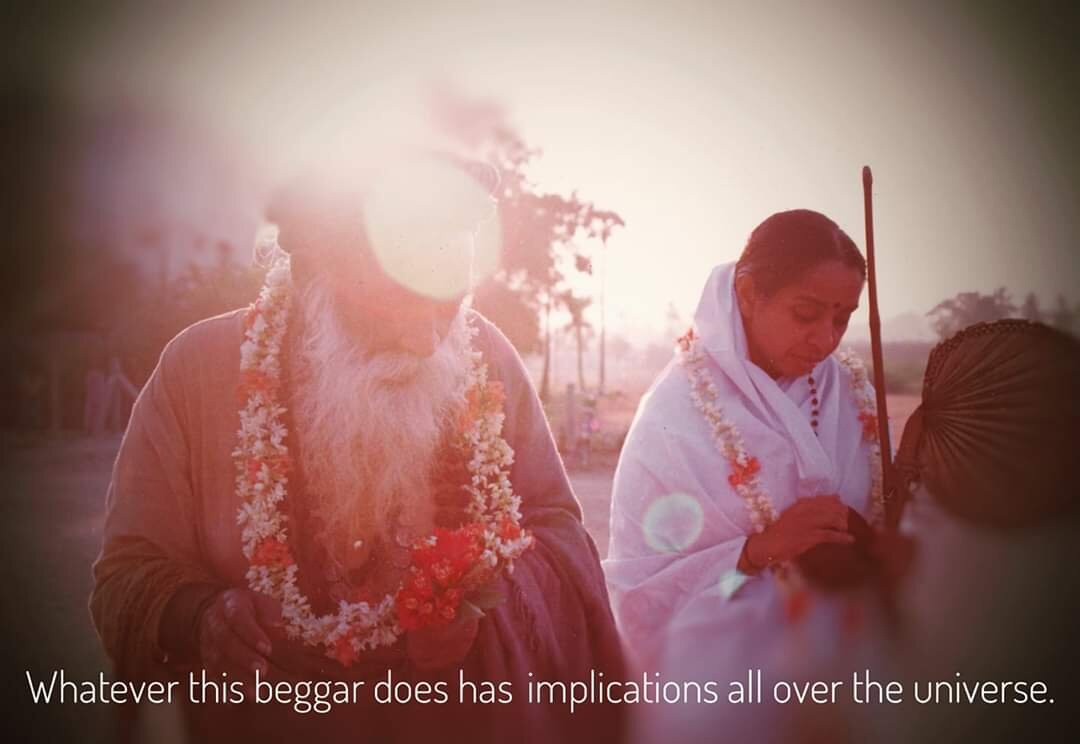

Sanatan Das Baul, Bengal, India, 2008

Having just arrived from the urban conflagrations of Mumbai, Varodara and Ahmedabad, I was feeling sensitive to the decline of sacred culture and natural environments so evident in the cities of India today. Even though I had traveled in India several times before, to my Western sensibility it seemed improbable that this water--littered with refuse and darkly glowering--could be fit for any use. For the Bengalis, it is still sacred.

Even with the all-pervasive influence of Western techno-culture, Kolkata is a place of ancient rhythms and flows. The first strong impression was that this is Kali’s playground; Kolkata is a city in which the ista devata (chosen deity) is alive and thriving, where shrines to Kali Ma adorn every other street corner. There she resides in ecstatic four-armed form with lolling tongue and primordial eyes, beautifully adorned and freshly garlanded with marigolds and red hibiscus flowers; ghee lamps burn brightly at her feet in the smoky, soot-blackened air while people hurry past, wrapped in shawls against the chilly night air.

In Kolkata, you would do well to pay your respects to the Mother Goddess as soon as you arrive, and indeed, Kalighat was calling me. Kali’s influence brings the transient nature of all things into sharp focus on the streets where life unfolds, where her images remind us that this fragile existence—miraculous in its exquisite beauty but also raw and cruel—is ephemeral.

Gour Khepa Baul (right), Kolkata, January 2008

I was traveling in Bengal with Baul Khepa Lee Lozowick and his blues band, Shri, on a two-week performing tour in Kolkata hosted by Purna Das Baul. Lee was bringing traditional American blues and rock & roll to Bengali audiences in ten concerts in the Kolkata area, some in conjunction with Purna Das and his clan. Along the way we found ourselves connecting with Bauls from diverse places—from the vast sprawl of Kolkata to rural West Bengal, Shanti Niketan, and Tarapith in Birbhum. Dressed in pale orange or pink and wearing a handmade patchwork jacket, long hair pulled up and rolled into a knot on top of the head, with ektara or anandalahari in hand, wherever Baul musicians gathered to play their songs and dance there was a sense of freedom and elation. And yet, as Lee commented, “If there is no yoga, there is no Baul.” And so, after making yatra (pilgrimage) to Dakshineswar and Kalighat—once of the most ancient temples dedicated to Kali—we turned to the primary mission of our sojourn: encounters between the Bauls of the West and the Bauls of Bengal.

Who are the Bauls? What is it about them that so easily captures the contemporary imagination? For centuries Baul bards, yogis, and mystics have wandered the dusty roads of Bengal, going from village to village to ply their spontaneous and simple art, sing songs and dance with joy. In this way, they uplift the ordinary person with their poem-songs, transporting the listener above the daily grind for survival and into a direct experience of the sublime.

In more recent times, the Bauls have thrilled their audiences—both East and West—with their evocative songs, their symbolic garb and ektara, their enigmatic spirit and unique style. Their iconic image is unmistakable, but this is only the surface appearance of a profound way of life. The Bauls are carriers of deep secrets, and in order to make sense of what they do, or the enigmatic twilight language of their songs, one must dive into the traditional underpinnings of Baul sadhana, or spiritual life.

“They came, they sang and danced, and they disappeared into the mists.” Perhaps it is the poetic interplay between the sahaj perception of beauty and impermanence that makes the elusive Bauls so compelling. Far from the clamor and complexity of today’s Kolkata, with its fast-paced, thick amalgam of modern and ancient ways of life, the Bauls of Bengal have flourished despite calumny, criticism, poverty, and hardships of all kinds. Walking the razor’s edge between joy and sorrow, love and loss, the Bauls have a way of life that has endured at least five hundred years and carries a vitally necessary message—like a refreshing wind—to our current times, when the need to rediscover the timeless truths of ancient cultures is so crucially important. The Baul Way tells us that reconnecting with our individual sahaj nature is the only way out of the dilemma in which we are mired; to do this, we must begin to remember the naturally ecstatic primordial essence—an innate blueprint of dignity, beauty, and wisdom—that underlies the personality and habitual social conditioning of every human being.

A true Baul is a spontaneous occurrence, an uprising of the Divine within the evolutionary pulse of Nature. The Baul spirit arises in all cultures, in all times and places throughout history. “Baul” is simply a word—meaning “mad,” or “taken by the wind”—to describe a phenomenon of consciousness that is often called “divine madness.” If we look closely enough in diverse cultures and times throughout history, we can notice or identify many in whom the heart of a Baul beats softly or wildly. Artists, healers, poets, musicians, great spiritual teachers, geniuses, leaders in any field—many of these great ones show the strains of the iconoclast, the rebel, the lover, the mystic, the visionary, the radical prophet. A Baul exhibits many or all of these qualities, cultivated and aimed toward the fulfillment of one purpose—to gather honey for the love of the Lord. Or, to say it in another way, and as Khepa Lee hinted in the quote at the beginning of this introduction, for the enjoyment of the Supreme Being.

To rediscover and connect with this inner nature, the Bauls cultivate a spiritual way of life in which signature themes come into play:

God is Real—a direct relationship with a personal deity or God (ishta devata).

Sahaja—a profound trust in the innate, pristine nature of the human being as divine.

Guruvada—The way of the guru; reliance on the guru or spiritual preceptor.

Bhava—the cultivation of divine mood (bhava) and rasa (taste, juice, elixir) as a means of communion with the personal Beloved.

Renunciation—disidentification with social, familial, and religious identity and customs.

Beggary—the foundation of a life surrendered to the Will of God.

Poetry, song, and dance—dharma expressed in art and aesthetic appreciation.

Kaya Sadhana—spiritual practices based on the innate wisdom of the body, including yogas of sex and breath.

It is these facets of the essential sahaj vision that American Baul Khepa Lee Lozowick (1943-2010) recognized as extraordinarily similar to the teaching and practices that evolved after a spiritual awakening irrevocably changed his life in 1975. This resonance was so powerful that in 1985, in answer to a new student’s question—“What should I say is our tradition?”—he said, “Tell them we are Bauls.” It was a turning point, in which Lee’s statement—part declaration, part prophecy—not only named but provided movement and fuel to the development of the sampradaya of Bauls in the West, also known as the Hohm Community.

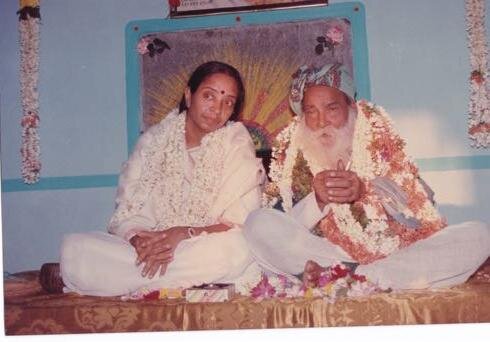

Khepa Lee Lozowick with Gour Khepa Baul, Kolkata, January 2008

At first the connection seemed very mysterious, but as the years passed and the Hohm Community evolved over time, the similarities became clearer. Foremost, like all Bauls, Lee was extraordinarily devoted to his own guru, Yogi Ramsuratkumar (1918-2001), the revered beggar saint of south India, with whom Lee shared a life-long, intimate, and loving relationship. By 1988 it had become clear that Lee was walking the guruvada, or way of the guru. As the years progressed, this took on many subtle nuances that can be found in the three large volumes of Lee’s poetry written to his master. Extraordinary as well was the fact that Yogi Ramsuratkumar blessed the teaching work of his American devotee unequivocally, including Lee’s poetry, music, and rock & roll, as well as his affiliation with the Bauls of Bengal and his relationship with Sanatan Das Baul in particular.

Today, the Western Bauls are a loosely organized (and unorganized) sampradaya (spiritual clan) of sadhikas and sadhakas who have dedicated their lives to the teachings and practices given by Lee. While there are notable differences between the Bauls of the East and West in terms of the way these essential teachings and practices are lived—as is only natural, due to the vastly different milieus of culture and era—perhaps the second most obvious of these common elements is the emphasis on guruvada, or radical reliance on the guru, which is inseparable from the ishta devata (chosen deity), and the central importance of bhava, or divine mood, as the means to communion with a personal Beloved.

Amongst Bauls, the cultivation of bhava is sometimes referred to metaphorically as gathering honey for Lord Krishna; bhava is cultivated through numerous means that involve rasa, or the many flavors and tastes of the Divine manifesting on Earth. For the Western Bauls, this includes music, dance, feasting, sexual sadhana in committed relationships, friendships, and the parent-child relationship, as well as creativity and all artistic endeavors, love of nature, aesthetic appreciation, contemplation, meditation, and prayer.

The Raas Leela

The Baul Path is a tantric path, and on all tantric paths no aspect of life is rejected but is used or entered into as a potential realm of experience from which spiritual value may be extracted. At the same time that nothing is rejected, it is equally important on the tantric path for a sadhaka (spiritual practitioner) to make clear distinctions, for there will inevitably be aspects of life experience that one wisely chooses not to engage—not out of rejection, fear, piousness, recoil, or judgment, but because it is simply not profitable to one’s aim, which means that engagement with a particular experience or event will not yield positive influence or momentum for the purpose of the Path in one’s individual case. This could be called developing discrimination and learning the wisdom of one’s svadharma or personal dharma—a concept that will be explored in later pages.

Interviewing Gour Khepa Baul and Durga Dasi (with Khepa Lee Lozowick), Kolkata, January 2008

The spiritual way given by Western Baul Lee Lozowick is passionately engaged with the Divine in a way that is unabashedly theistic and fueled by direct experience. On a path in which the personal Beloved is a vivid and real relationship, what “feeds” or attracts the Supreme Being is of supreme importance. As Lee wrote, God would like to enjoy His or Her creation—it could be said that God has a sweet tooth! Like a bee is drawn to the sweet nectar of the flower, the deity, however imagined, has a craving for the many nuances of rasa, or tastes, of devotion, harmony, peace, kindness, love, gratitude, praise. In the words of the poet, we may speak in terms of potent substances such as honey, syrup, nectar, juice, ambrosia, elixir, pollen, sugar, morning dew, wine and sweet liquor, kisses, and many kinds of bodily fluids.

And so, we will find in the world of our Baul poet—Khepa Lee—there is a direct relationship between sweetness, sexuality, and song, between rasa, rupa (bodily form), and rock & roll—the Western Baul equivalent of poem-songs that transmit the secrets of Life. All of this, as we will see, is synthesized and blended into the bhava we call “praise,” which pleases the Divine above all other potentialities.

Though much better known in Europe, in many ways, Khepa Lee and his teaching has remained one of the best-kept open secrets of the spiritual scene in the U.S. in the thirty-five years since the beginning of Lee’s teaching and working with students on the East Coast in 1975. The time has come to make Lee’s message more available to those who feel the inner call of longing. If this small taste whets your appetite for me, please check out my book, The Baul Tradition, which aims to distill the essential elements of the Western Baul Way. Such a distillation is not an easy task, for while Bauls are simple, earthy, and natural, their way is iconoclastic, deep, rich, complex, multifaceted, and multidimensional. In general, a true Baul defies definition and prefers to remain fluid and authentic to the awesome raw potential of the moment at hand. And as you learn more about the Bauls, both East and West, keep an open mind.

Further Reading …

To enjoy reading more about the lineage of Khepa Lee Lozowick, Yogi Ramsuratkumar, and Swami Ramdas or the Bauls and Sahaja in the East and West, see my articles published in Namarupa Magazine:

Issue 14, Volumes 5-6 — “Remembering Lee Lozowick” (2011)

Issue 8 — “Yogi Ramsuratkumar” (2001)

Issue 9 — “Heart on Fire: The Bauls of Bengal” (2008)

Namarupa Magazine has been a source of inspiration for me for many years. Their commitment and integrity to the Indian traditions, sadhana and the spiritual path stands out as a beacon of light in the world today. I’m pleased that my work is represented in their publication. Back issues are available through Namarupa.

Ma Devaki

Devaki Ma was born on January 4, 1952, in Thanjavur, Tamil Nadu, of middle-class Brahmin parents. Well-educated, with an advanced degree in physics (Master of Philosophy), she was senior lecturer in physics at Sri Sarada College in Salem, South India at the time of her historic pilgrimage to Tiruvannamalai in 1986 when she met her Master, Yogi Ramsuratkumar. Devaki Ma was named by Yogi Ramsuratkumar as his “Eternal Slave” for the unwavering devotion and constant care she gave to him throughout his life. He took Mahasamadhi in 2001, and is entombed in the temple of his ashram. Devaki Ma continues to live at the ashram where she maintains a life of constant spiritual practice and service, inspiring all her Master’s devotees, and all who visit this sacred site. yogiramsuratkumarashram.org

Ma Devaki

With Devaki Ma in Tiruvannamalai, 2018

On pilgrimage in 1993 with Lee was the first time I met Yogi Ramsuratkumar. We spent three full, rich and unforgettable days with the Godchild of Tiruvannamalai, mostly on the porch of Sudama House, where—after a serious illness in which he had almost died—he had just moved into residence with three of his close women disciples, Devaki, Vijayalakshmi, and the two sisters, Vijayakka, and Rajalakshmi. Devaki Ma had just been named by Yogiji, “My eternal slave.” During our visit she sat beside Yogiji and attended to his needs and wishes, which included reading many of Lee’s devotional poems written to the “Mad Beggar” Yogi Ramsuratkumar, who listened with tears in his eyes. Over the years Devaki and Vijayalakshmi (pictured below with Yogi Ramsuratkumar) witnessed the lilas, the singing and dancing, the laughter and the tears of my personal experience of Bhagwan Yogi Ramsuratkumar, in the company of my teacher, Lee. A spiritual friendship of deep respect, honor and appreciation between gurubhais—a rare treasure and a blessing—evolved over the years and especially during the last year of Bhagwan’s life and in the next two years while I wrote Under the Punnai Tree (Hohm Press, 2003), the first biography published in the West of the beloved saint, Yogi Ramsuratkumar.

Parvaty Baul

Parvathy Baul is a Baul folk singer, musician and storyteller from Bengal and one of the leading Baul musicians in India. Trained under Baul gurus, Sanatan Das Baul and Shashanko Goshai Baul in Bengal, she is the most recognized woman Baul performer in the world. Parvathy Baul is a practitioner, performer, story teller, painter and teacher of the Baul tradition and has performed in over forty countries, in many prestigious concert halls and music festivals. In February 2019 , she was conferred Sangeet Natak Akademi Award , by Government of India for her contribution to the ancient Baul tradition. She is now creating a dedicated learning center for Baul tradition in Bengal. parvathybaul.com

With Parvaty Baul, Guru Purnima, France 2019

In January 2008 I had the opportunity to witness a powerful reunion between Khepa Lee and Sanatan Das Baul and his clan in Kolkata, Bengal. At that time I interviewed Sanatan Baba (published in my article in Namarupa, 2008, and in my book The Baul Tradition, Hohm Press, 2014), made possible only by the efforts of Sanatan Baba’s skilled and succinct translator and senior disciple, Parvathy Baul, who would become his lineage holder a few years later. Meeting Parvathy was revelatory for many reasons. Her artistic rendering of Baul poetry/songs in sacred performance ignited my heart with the flame of her passion for the path of the Bauls. With a voice that soars to heaven and beyond, even while her feet are planted on the sacred earth and move in the rhythms of her dance, Parvathy has inspired me time and again over the years. Parvathy sheds a bright light on the essential teachings and practices of the Baul Way, which profoundly enriched and inspired my book, The Baul Tradition: Sahaj Vision East and West. Since that time our relationship has flowered into a beautiful expression of spiritual friendship between practitioners on the Great Path.